오산기지 1953-54 이시우 2006/05/09 1679

http://kalaniosullivan.com/OsanAB/OsanSongtan1-1.html

1953:

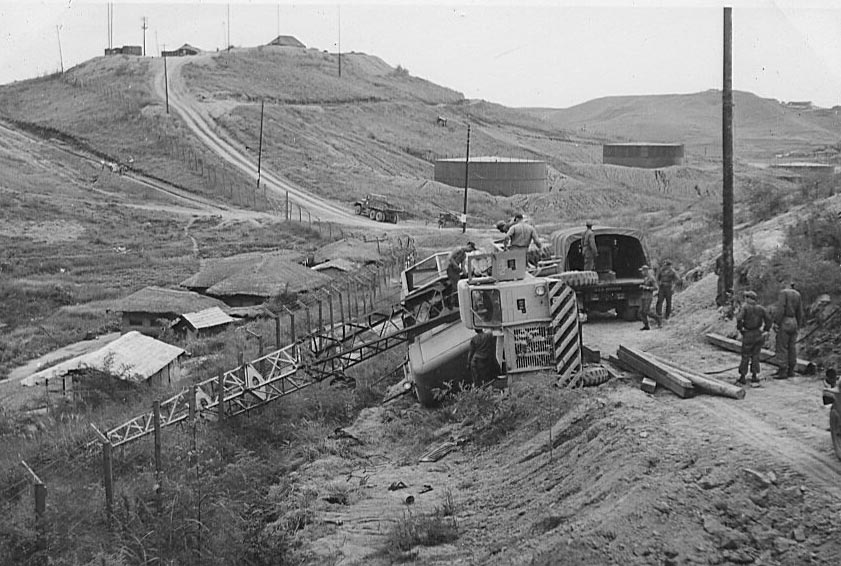

Indigenous Workers Flock to Area As soon as the base construction started there was a need for indigenous workers to do the coolie labor — hauling of rocks and dirt. The Army 839th Engineering Aviation Battalion hired some Koreans to work in their mess halls. In addition to the prostitutes off-base, the area started to fill with people seeking work on base. On the hills of the anti-aircraft artillery sites, little kids were filling sandbags for 25 cents a day. The refuse was contracted out — and the response was that the garbage collectors were eating the American garbage as they drove away.

As word spread, many North Korean refugees from Hwanghae-do in the southwest part of North Korea moved to Songtan. These people had fled on foot and ended up in Taejon until the threat of the Chinese invasion had subsided. When the base was started in June 1952, the destitute North Koreans sought work at Osan. They arrived in large numbers and huddled together in the Milwal-dong area for protection and morale. As more arrived, they spread along the south-side of the perimeter into Jeokbong-ni, Sageori, Pokchang-ni and Shinchang-dong. Without land or resources, they took on the menial of tasks of the community to survive. The large numbers of refugees started to tax the school system in Seojong-ni as there was compulsory elementary education for children.

Everyday people seeking work on the base would line up at the main gate. A truck would drive up and count off how many laborers were needed for the day’s work. At the end of the day, the workers were paid and delivered at the main gate. Later a contract office would be setup for the 839th Engineering Aviation Battalion and 914th Engineering Aviation Group which would handle the jobs as contract work. Photos of the construction of the base shows Koreans working as coolie laborers digging into the hillside and hauling the rock and dirt away on A-frames (chige). In the construction of the runway, Korean workers were engaged in the simple tasks to assist the EAB in pouring the concrete.

Koreans were hired as mess workers and other jobs requiring no technical skill. Korean companies would be used for the completion of small jobs, while the EAB handled the major tasks. At the time, the EAB was more concerned with constructing the essential base infrastructure rather than “morale” facilities. These smaller facilities would be done under contract.

As the base started to take shape, other areas were opened to indigenous workers. They worked in the messes, cleaned barracks, and did the laundry. These workers, in essence, liberated the officers and enlisted force from the everyday drudgeries of military life. Road gangs were comprised mostly of women as the men had all been conscripted or killed in the war. The base roads were cut out by graders driven by GIs, but right behind them were road crews with A-frames (chige) on their backs hauling the dirt away and widening the road with pick and shovel.

The fortunate ones who spoke a little English found jobs as translators/clerk typists in the units; or bartenders/waitresses in the clubs. There were few openings on the flightline area except as general cleanup people and as manual laborers used in moving munitions or working base supply in the storage facilities. (NOTE: It should be noted that the Christian missionaries in the Pyeongyang area had been teaching the poor and disenfranchised Koreans English since the late 1800s. Many of these Koreans migrated to America as “scab” laborers to offset the Japanese workers who started to leave the plantations and farms. As a general rule, the majority of the lower class people who could speak English were both Christians and North Korean.)

At times there were saboteurs amongst the Korean workers which increased the Americans mistrust. Dick Clifton, a South African pilot, remembered one occasion when a Korean worker removed the safety clip on the arming wire of one of his bombs — a move which armed the bomb and nearly blew up him and his plane. The air police caught the saboteur soon after this episode and “dealt whith him appropriately.” Presumably they shot him because summary executions was the standard procedure by the ROK Army who handled security. (Flying Cheetahs, Moore and Bashawe, pp213-214) However, in many cases, these saboteurs were in actuality people simply seeking to engage in thievery — but the consequences were the same when caught — summary execution. Of course, the rumors of the frequency of these occurrences heightened the mistrust.

Spies were also a problem throughout Korea — especially in the early years of the war. Many Koreans could speak some English because of being taught in missionary schools — mostly in Pyongyang. Unfortunately, these students were also from the disenfranchised peasant class who were Communist in leaning. Because of their English skills, these people easily found employment in the squadron bars and officer clubs where they could listen in on conversations. They were occasionally found and summarily executed — on the spot. Though some Koreans were used in administrative roles, they were kept away from sensitive material. By 1953, the threat of spies had decreased — though it would remain an open problem for American bases well into the 1970s.

There was a generalized prejudice against the Korean workers by Americans. Many of the Americans didn’t like the Koreans and called them “Gooks.” The Americans felt they would steal anything that wasn’t nailed down. At this time, there was desparate poverty off-base and starvation amongst the populace. Instead of seeing the people’s thievery as simply a means of survival, many Americans perceived it as a “colonial mentality” on the part of the Koreans whereby stealing from the Americans was morally acceptable — while stealing from Koreans wasn’t.

Cultural sensitivity was lacking for the most part in the Americans. But to come to the American defense, the landscape around Osan was barren of any trees. The air stank from the use of human excrement for fertilizer. The people were in rags and poverty was everywhere. The response was that the kimchee, the national dish, stank and there wasn’t a damn thing in Korea worth saving. Though the country had thousands of years of history, none of it was evident in 1953 — except ruins. Unlike Japan, it was hard to feel an affinity for this country or its people.

Despite this fact, many Americans took a shine to the Koreans who worked on base. In some cases, the Americans would “adopt” an orphan and he would become a fixture on the base — residing in the barracks as well as acting as a houseboy. Unfortunately, their attitude towards the Koreans were for the most part paternalistic. Some units allowed their “mascots” (orphans) to sleep in the barracks. But though the Americans thought of their houseboys as lowly workers, the truth was that they were paid about $30 a month ($1-2 for each barracks resident) which was $6 more than a Korean colonel made. Having a job on base was a blessing. Soon the Korean workers formed networks whereby other family members would be brought in to work on base.

Regardless, the Korean people remembered the Korean War veterans and passed legislation whereby a foreign Korean War veteran could buy Korean land without being a Korean citizen. Though few took up the offer, some did and became Korean citizens after the war. The Korean War veterans who returned for the 50th Anniversary of the Korean War were treated as honored guests. The Koreans remember the sacrifices of the Korean War veterans in assisting Korea during its time of national need.

C-Ration Village Outside the Gate (1954) (Robert Furrer)

In the photo above, the area that became known as Chicol Village (also known as Jae Yok-dong) — and finally Shinjang-dong. To the local residents, it was known as Chongmun-eup (Front Gate town) to differentiate it from the agricultural village.

The photo was taken just at the main gate — most likely from the helipad to the right of the gate. To the right there is a sign post where the Korean to the right is. At the sign post was a small alley that ran down towards the Jungang Market area — which still hadn’t been established — and then down along the rice paddies in what is now Shinjang 2-dong.

The Shinjang Mall Road — though it was not a Mall then either — veered left at the main gate and then jogged right. It straightened out till it went up the hill and over the rail spur. It then went down over the Kyongbu Railway. If you look to the left, you will see the pattern of the houses with a space between indicating the two-lane dirt road. The houses-shops were built directly along the edge of the Shinjang Mall road and there was very little expansion as yet.

The clap-trap nature of the houses are evident. The roofing material most likely is tar paper (obtained from the base) and tacked down with strips. The tar paper was used for inner wall water barrier insulation on the Jamesway buildings and Quonset huts used on base. These houses shanty houses made from mudwattle and scrap wood — even cardboard.

In between the houses, you will note there is an open strip along the hillside. This is the location of the Kyongbu Railroad line and railroad spur area to the base. The hill in the background is the hill between the base and MSR-1. There is a faint line on the hill indicating the road that joins MSR-1 at the base of the hill. The Songbuk-dong business area and farmers market had not been built as yet.

——————————————————————————–

Education The influx of refugees into the Chicol-ni and Milwal-dong areas created problems of overcrowding in the local area schools. In Seojong-ni, there was the Seojong-ni Elementary which had been officially established in 1945 — but traced its roots back to 1922 Japanese school. The Seojong Elementary School had reopened after the initial invasion in Jun 1951, but there were not enough teachers and too little classroom space in their 3-room school house. In April 1952, a Parent-Teacher Association was formed to help defray the costs. Under this program, the PTA supported about 75 percent of the costs and the government provided 25 percent. Unfortunately, under this plan only those who supported the school would attend. Though primary school was made compulsory in 1949, there were still disenfranchised children in the refugee community.

NOTE: In 1952, Robert Evilsizor, 839th EAB, took 8mm home movies of school children marching in line to school and a boy in uniform playing “changi” (kick-toy game). The neatly dressed children we believe were headed to Seojong-ni Elementary about 2 km down the road. There is a part with a little boy in uniform that we believe was from the St. Theresa’s middle school — taught at that time by Father Dominicu in the St. Theresa Rectory. We make this assumption because of the uniform. At that time only middle school (and above) students wore uniforms. St. Theresa’s was the only Middle School in the area in 1952. In 1953, it would move into its new 8-room school house built on the church grounds capable of supporting 280 students. (St. Theresa’s later became the Seojong Catholic Church.)

Within the area, there was the Kumgak-ri School was opened up in 1953 as a “branch” of the Seotan Elementary School that had been established in 1930. In Jinwi, there was the Sadae Elementary (later the Jinwi Elementary).

Education in Local Area

Bob Spiwak sent a photo taken in 1953 that he at first thought was an orphanage, but then realized it was school kids. (NOTE: We at first thought it was Seojong-ni Elementary, but the date didn’t match. Then we noticed the correlation of Kumgak-ri Elementary on the southwest side of Hill 180 being attached to Seotan Elementary in Nov 1953 — and thought it was the school built by the 18th FW in 1953 with donations. Again we were wrong as Bob Spiwak said it was easy walking distance from Hill 170 on the northeast side of base. Later Bob confirmed that the building was NOT Seojong Elementary. As of Aug 2005, we are not certain of the school, but Mr. Oh Sun-soo stated that the construction appeared to be Japanese.)

His photo is of significance as there were few photos of these types of structures and infrastructure at the time. At that time, this school was not considered important. What is marvelous about the photo is that though the kids had patches on their clothes — all the clothes appeared washed and pressed. This reflects the attitudes and respect towards the educational process on the part of parents and children — a tradition continued till today. There was no middle school or high school in the area and for many of these kids — this was the end of their education. The intent of these schools was to teach the Koreans to once again read “hangul” (Korean) — after years of Japanese colonial rule which banned the use of Hangul in schools in 1937 — and it succeeded as the Korean populace currently has a 98 percent literacy rate. Because of the times, this would be the last education for many of these children as poverty prevented many from continuing on.

School unknown, but near Hill 170 (1953) (Bob Spiwak) (NOTE: See Compulsory Elementary School Education in the Songtan area for details.)

In 1952, Robert Evilsizor with the 839th EAB, took some 8mm movies of a long procession of kids walking to school. As there was only the Seojong Elementary School in the area at the time, these kids must have been on the way to school. They were guided by the teacher and some women who might have been parents or teachers. Though the government had passed a law making education compulsory it did not fund the schools adequately. Thus most of the schools were supported by “donations” from the Parent-Teacher Associations. In fact, those children whose families could not afford to “donate,” did not attend school. Because of the severe poverty, many times families could not even afford the cost of paper and pencils. In the film, most of the children did not have uniforms, but some of the older one did. Some of the girls wore white blouses with black trim on the collar and black skirts. Some of boys wore the traditional black coat and pants. What was evident was the happiness to attend school that was evident in the faces of the children as they marched along.

Though elementary education was “compulsory,” the truth was the government had neither the resources nor the teachers to implement such a program. At that time, if you were a high school graduate, you were qualified to be a elementary school teacher. “Government-endorsed” schools were set up in a system where the government would provide the buildings (many times tents donated by the American military) or unheated-buildings and approximately 25 percent of the funding. The parents would “donate” the difference. In this void many missionary and church schools moved in to fill the void to help the poor people be educated. The missionary schools have a long history in Korea dating back to the late 1800s starting in Pyeongyang and spreading to the other major cities and treaty ports. At that time, the yangban upper classes were educated, but the poor were left uneducated. The same appears to be true in the Songtan area in the 1950s. The “haves” (no matter how meager) went to the government schools, while the poor went to the “church” schools. The emphasis was simply on learning to read and write Korean, but the education starved Koreans flocked to these schools which operated sometimes in shifts to handle both children and adults.

The Seojong Elementary School that was first established in 1945 as a “branch” training school and became the Seojong-ni Elementary School in 1949. This is the school that was over-loaded with students in 1952 when North Korean refugees flooded into the area seeking work at the Osan-ni AB. As the North Korean population exploded in the area, the Kumgak-ri Elementary School was established to the south of the base as a “branch” school of Seotan Elementary School in 1953.

However, there were also “church” schools in the area. The most visible was the Salvation Army was active in the Chicol Village area. Its main work was with the orphans through the Gusegun (Salvation Army) church set up in the area. (NOTE: The during this time period there were 20 orphanages in Suwon and three in Pyeongtaek to handle the overflow crowds of children. The Pyeongtaek orphanages handled the orphans that showed up at K-55. Currently there is the Ae Hyang Orphanage in Seojong-dong run by Mr. Lee Min Ho.)

The Catholic church was started in Seojong-ni in 1930 and it appears that classes were taught in the rectory of the church to a small group of children by the priests. In 1952 Father Dominicu held classes in the rectory for children who sat on the floor. Through donations of the 18th FBW in 1953 from the Catholic personnel on Osan-ni AB, the St. Theresa’s Middle School was established. This was the forerunner to the Hyomyung Middle School and Hyomyung High School which have continued in operation to the present day. The Hyomyung Middle School celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2003 and the High School in 2006. (See 18th FBW builds country school for details.)

The Kwangmyeong Gongmin Hakkyo (church school) was established in 1953. The Taegwang Middle School authorities state it was in the same area as the Taegwang Middle School today — near the high ground next to the rice fields. The hakkyo was located below the area where Songshin Elementary was built in 1963. It was in the low-lying area adjacent to the rice fields.

(NOTE: The school taught the first three grades of elementary school. According to Mr. Pak Chong-su, owner of the Pak Toy and Doll Shop, the school was started by his father. Pak Song-chul, was an advisor to the 18th ABG Commander and got the base to provide the tents for the much needed school as the population swelled with North Korean refugees. The day-to-day operations was handled by Mr. Pak Byong-kwon, a good friend of the senior Mr. Pak, and who had a house adjacent to the school. (Source: Verbal conversation Kalani O’Sullivan and Mr. Pak Chong-su on 19 Nov 2005.

On 11 Nov 1955, the Songtan Godung Gomin Hakkyo (church middle school) started six classes. This became the Songwang hagwon on 6 Jan 1962 and then merged with the Songwang Middle School on 17 Mar 1962. On 12 Mar 1968, the Taegwang hagwon changed to the Taegwang Middle School and supplanted the Songwang Middle School with permanent structures next to the Songshin Elementary School.)

——————————————————————————–

18th FBW Builds Country School through Donations A HQ FEAF, 5th Air Force news release on 22 Jan 1954 read in part: The airmen of the 18th Fighter Bomber Wing provided materials and finances for a new eight-room country school house near Osan for 280 Korean grammar school children. While Korean builders speeded the construction of the new building, men of the 18th Wing utilized their off-duty time in the base hobby shop making 90 double desks and 140 double seats needed for the students.

Chaplain (Maj) Rinkowski and St. Theresa’s Middle School (1952) (Hyomyung 50th Anniversary Book (2003))

The Hyomyung Middle School 50th Anniversary Edition (2003) shed light on this school. The postcard in the photo reads: “This school was built by Catholic Airmen, Army Personnel, SCARWAF Personnel of K-55 through their generous contributions at Masses during the past six months. Bishop Paul M. Rho, Bishop of Seoul, (blocked out) the $6,000 (blocked out) 6 January 1954.” According to Mr. Kim Jong-youp, Vice-Principal of Hyomyung Middle School, the structure was built in what is now the parking lot of the Seojong Catholic Church.

However, though the postcard states the name as “St. Theresa’s Middle School,” the Hyomyung Middle School chronology shows that the school was called “Hyomyung Godung Gomin” — translated as a “High School Catholic.” It states that it was a 3 classroom building with the first principal Yu Su-Jong (Father Dominicu).

It $6,000 — a significant amount of money at that time — was donated by the 18th FBW Catholic Chaplains Fund towards the construction of the school done under contract, The key man in getting this going was Chaplain (Major) Rinkowski of the 18th FBW and Father Dominicu (Korean priest) of the church in Seojong. However, this project was not well-publicized and may have been a strictly Catholic airmen initiative as many veterans of that period did not know of this school.

Prior to this structure, Father Dominicu (1918-1977) was teaching a small number of students in the rectory in 1952. Father Dominicu served in the Seojong Church from 1952-1960.

Father Dominicu teaching in Rectory (1952) (Hyomyung 50th Anniversary Book (2003))

The building was erected in 1953 and called “St. Theresa Middle School” — or Hyomyung Godung Gomin (Hyomyung Catholic Middle School) — and is the predecessor of the present Hyomyung Middle School.

The Hyomung Middle School was founded on 21 May 1953 — and followed by the Hyomyung High School on 21 May 1956. (NOTE: It appears that the date of the official opening of the structure by Bishop Paul M. Rho is used as the founding date of the Hyomyung Middle School, though the school was established at a later date about a mile down the road.)

According to the History of the 18th Fighter Bomber Wing 1 Jan 1954 to 30 Jun 1954, Office of the WIng Chaplain, written by 1st Lt. Andrew J. McLean, Deputy Wing Chaplain, and signed by Bernhardt G. Hoffman, Wing Chaplain talks of the St. Theresa’s school. From this history, it appears that the funding and donations of time and effort for the construction of the furniture was solely due to the Catholic personnel on base — and did not involve the Protestant group. There were over twice the number of Catholics (12,219) on base as there were Protestants (5,339) and Jewish (40). At this time, the Protestant Chaplain was attempting to set up a Wing Orphanage Program, but there appears to have been a lack of support from the wing leadership. Wing Chaplain Major George M. Rinkowski who had initiated the action had rotated to the states in Apr 1954. At that time the Protestant Chaplain Program was attempting to start a program to direct its funds to a dedicated orphanage in the area, but it still had not gotten off the ground. A local minister, Kim Yung-Chul, conducted services for indigenous workers and conducted daily bible study classes. (Source: 51st FW/HO)

Humanitarian Services:

a. The Catholic Chaplain’s Fund sponsored a primary and middle school at So-Jong-Ri, Korea. The present building and equipment were provided entriely through the contributions of the Catholic personnel on the base. Further improvements are under way with a view to extending the size of the school by three rooms through AFAK, and an additonal two rooms provided through the Fund, making it eight rooms in all. The expense of erecting the building will be assumed by the Fund. Over $6,000.00 has already been donated towards this project since January 1st. Another $6,000.00 to $9,000.00 expenditure is contemplated to complete the project.

b. Towards various charitable projects in Korea the Catholic Fund, besides the building of St. Theresa’s School, has contributed over $2,000.00. c. An expenditure, in additopm, from the Catholic Fund of $800.00 has been approved for the purpose of providing a playground for the children of St. Theresa’s School. d. The tuition for three (3) years each, amounting ot $360.00 for the education of two (2) Korean boys has been provided by the Catholic Chaplain’s Fund. (Source: History of the 18th Fighter Bomber Wing 1 Jan 1954 to 30 Jun 1954, Office of the WIng Chaplain)

On 1 Mar 1964, the Hyomyung Middle & High School moved to its present location about a half mile down the road from the Seojong Catholic Church. On 1 Mar 1981, the Middle School and High School officially split into two separate schools. On 20 Dec 1997, the Middle School constructed its main building.

On 6 Nov 2003, the Gym was rededicated as the Kwangamkwan Bldg — the 50th Anniversary Gym. On 17 Feb 2005, the 50th class graduated from the school — a total of 16,219 students from its beginnings. On 28 Feb 2005, the Dominiku Building was erected in honor of Father Dominicu (1918-1977).

Seojong Catholic Church Parking Lot (2005) (Kalani O’Sullivan) (NOTE: Site of St. Theresa’s Middle School in 1953.)

Seojong Catholic Church (2005) (Kalani O’Sullivan)

Hyomyung High School (2005) (Kalani O’Sullivan)

Amphitheater Hyomyung Middle School (2005) (Kalani O’Sullivan)

Hyomyung Middle School (2005) (Kalani O’Sullivan)

——————————————————————————–

Honcho Park The Airman Magazine in Sept 2001 ran a touching story of Pak Chan-yang’s flight to freedom and finally finding work at the Osan AB Messhall. (See Honcho Park).

When he was 15 years old, Pak Chan-yang’s life changed for the better. But it didn’t seem like it at the time, as he ran for his life.

It was early 1953 and the Korean War raged. The Paks were farmers in Unyulkun, a village in North Korea’s lush Hwanghae province. The teen had never been to school. Instead he worked the family’s small plot of land. That was all he knew. It was life under the yoke of communism.

The Paks hated communism. “It controlled us,” he said. “We wanted to be free.”

The fighting in the province grew fierce. Guerilla forces were active. And as North Korean and Chinese forces closed in, the Paks knew there would be retaliations. So they fled.

Pak Chan-Yang (2001) (Airmen Magazine)

They made a beeline west for the Yellow Sea. They joined a ragtag exodus of refugees going the same way. All hoped to make it to safety, somewhere. On their heels were the communists who’d been their masters since the end of World War II.

But the Paks were lucky. American ships waited at the coast to take the refugees to safety. The Paks boarded a huge landing craft. People crowded into every available space. None had any idea where they were going. But Pak said that didn’t matter.

“All we knew was that we’d never be able to go back home,” said Pak, now 63 and head chef at the dining facility at Osan Air Base, South Korea.

However, as he looked out over the sea, Pak did wonder what lay ahead. What would happen to his family. About the family left behind that he’d probably never see again.

“We were scared,” he said. “But in our hearts, we knew leaving was the right thing to do.”

Flight for life

The journey to the South was a desperate flight of survival. A trip made by hundreds of thousands of North Koreans. It was one of many sacrifices they’d make to better their lives.

Two days later, the ship docked at Kunsan City, and Pak’s new life in South Korea began. Within a few months, the fighting stopped. An armistice followed. Then both sides sat back to maintain the shaky cease-fire.

Pak’s family settled in Kunsan, and still live there. But the teen-ager knew he had to strike out on his own. What little money his father had would soon be gone. He’d been free six months when he heard the Americans were hiring people at Osan. He knew he had to go there.

“It was the only way I could help myself and my family,” he said. “I had to go.”

So with the few won [Korean money] that his father had given him in his pocket, he left. The money didn’t last the trip, but he made it to Osan. What he saw amazed him.

The base was still under construction. And jets took off with a roar from its concrete runway. The landscape around the base was bare. There were no rice paddies or trees. No town or homes.

“I had never seen anything like it before,” he said. “But there was so much going on.”

Out of money and hungry, he joined the other people outside the base gate looking for work. He spoke no English and had no job skills. But he was determined. During the next three months, he lived day to day. If he got a meal a day, he was lucky. Many days he went hungry. He built a shack from cardboard boxes discarded from the base. But each time it rained he had to rebuild it.

“And it rained a lot,” he said.

Pak doesn’t like to dwell on that time. All he’ll say is that it was a hard time.

Pak doesn’t like to dwell on that time. All he’ll say is that it was a hard time.

He got his break in January 1954 ?a job helping build the base dining facility. He had an income. Could eat regularly and send his family money.

Pak Chan-Yang (2001) (Airmen Magazine)

Pak Chan-Yang (2001) (Airmen Magazine)

When the dining facility opened, he stayed to work in the kitchen. Soon he developed a taste for roast beef and hamburgers. He’s been at Osan ever since, longer than any other worker. Forty-seven years later, “Honcho” Pak ?as his co-workers call him ?is head chef at Osan’s award-winning Pacific House dining facility. He’s done every job there from cleaning the kitchen and sweeping floors to peeling potatoes, managing the storeroom and cooking.

——————————————————————————–

18th TFW and 2d Squadron SAAF Transition from F-51 Mustangs

29 December 1952: The F-86-11 Mobile Training Unit (MTU) bagan arriving at Osan. Everything was in place by 7 Jan 1952, the unit having brought over from Chanute AFB, in Illinois. (Source: F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea, Warren Thompson, 1999, p28)

7 January 1953: The task facing Colonel Frank S. Perego’s 18th Fighter Bomber Wing was trmendous. It was expected to keep its old F-51 Mustangs in operation as long as possible while it moved to an unfinished airfield in the dead of winter and began to transition conventional fighter pilots to the “hottest” USAF jets. The conversion program was already lagging when the 18th Wing moved from Chinhae Airfield ot Osan-ni on 26 December 1952. No Sabres had yet been received, but the Mustangs were so worn out that the 18th Group moved such of these as it still possessed from Hoengsong to Osan-ni on 11 Jan 1953. After arriving at the new base, the 12th Squadron and the attached 2d South African Air Force Squadron stood down for transition, but the 67th Squadron continued to fly Mustangs until 23 January. On this day, the old F-51s — once the pride of the Air Force but now sadly obsolete old planes — were withdrawn from combat. (Source: USAF in Korea, Robert F. Futrell, pp637-638)

A mobile training detachment for the F-86 came from Tsuiki to Osan to begin the conversion training. It continued eight hours a day, seven days a week until the task was completed. Several experienced pilots from the veteran 4th and 51st Interceptor Wings were transferred into the 18th to ease the pilot transition. Sabre Jet Classics stated: “It would be no easy task for the South African air and ground crews to transition into the Sabre. None of the pilots had ever flown a jet, nor had any of the ground crews maintained an aircraft as complicated as the F86.”

Harold Snow and F-86F with early 18th FBW Tail Marking (early 1953)

(NOTE: Red stripes indicate the 67th FBS; Yellow Stripes indicate 12th FBS)

(Harold Snow, F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea)

Osan AB Sabre Jet (early 1953) (Ron Freedman)

According to The U.S. Air Force in Korea (p637), “The new model Thunderjets increased the Fifth Air Force’s combat capability, but the biggest news was the proposed equipment of the 8th and 18th Fighter Bomber Wings with F-86F Sabre air-ground attack planes. Except for bomb shackles, a modification of its gun-bomb-rocket sight, and special 200-gallon external fuel tanks, the F-86F Sabre-bomber would not be greatly different from the F-86F-interceptor. Many pilots were not completely convinced that the Sabre would be satisfactory as a fighter-bomber. “It’s much too fast,” some said. “It’s bound to be unstable,” thought others. Despite such pessimism, the Fifth Air Force planned to convert the 18th Fighter-Bomber Wing at the new Osan-ni Airfield, squadron by squadron, beginning in November 1952. Sometime in January 1953, after the 18th Wing had obtained its full complement of Sabres, the 8th Wing was to begin to convert its squadrons at Suwon Airfield. Conversion of air wings to a radically different type of aircraft is never an easy task, and a number of unforeseen developments made the Sabre fighter-bomber conversion program the most difficult. Slippages in deliveries of Sabres to the Far East delayed the 18th Wing’s conversion and put both wings into transition at the same time. Concerned with the growth of Red air capabilities, General Barcus ordered the new Sabre wings to make their pilots proficient in fighter-interceptor tactics before beginning fighter-bomber training.”

January 22: The 18th FBW withdrew its remaining F-51 Mustangs from combat and prepared to transition to Sabres, thus ending the use of USAF single engine, propeller-driven aircraft in offensive combat in the Korean War. Some of the F-51s went to the ROKAF, and the rest were ferried to Itazuke, Japan. The decision to reequip the unit with F-86F-30 Sabres was made in Oct 52, but problems with delivery had delayed the conversion. (Source: AFHRA) (NOTE: On 27 December 1952, No. 2 Squadron flew its last missions in the veteran F-51Ds. However, delivery problems held up the conversion to the Sabres until early 1953. On 30 December 1952, the 18th Wing moved from Chinhae to the new air base that had been built at Osan in anticipation of the arrival of the F86s.)

8 January 1953: 12th FBS stands down froom combat and flying their F-51Ds back to Kisarazu AB, Japan by way of Itazuke AB, Japan. With the 12th FBS ‘hitting the manuals’ by early January 1953, the Soth Africans became the nexxt unit to stand down. This left just the 67th FBS at K-46, flying as many missions as it could handle with all the wing’s surviving F-51Ds. (Source: F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea, Warren Thompson, 1999, p29)

12 January 1953: Heavy snowfall typical of December and January with temperatures in the teens or lower. The 12th and No.2 Squadrons received their Sabres, while the 67th, continued flying Mustangs.

15 January 1953: On 15 January the 67th launched its last major strike out of Hoengsong, the F-51s then recovering at Osan AB. This was a significant event in the history of the 18th FBW, for less than a week later (23 January 1953, to be precise, the 67th FBS flew its last combat mission of the war with the F-51D. (Source: F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea, Warren Thompson, 1999, p29)

23 January 1953: The 67th Squadron continued to fly Mustangs until 23 January. On this day, the old F-51s — once the pride of the Air Force but now sadly obsolete old planes — were withdrawn from combat. (Source: USAF in Korea, Robert F. Futrell, p638). The unit was then officially removed from the available frontline force. According to official records kept by the wing, 20 Mustangs were flown back to Japan on 17 January, with the remaining 26 fighters flying out from Osan. 11 days later: The retirement of the legendary WWII vintage fighetr from the USAF’s frontline force was carried out with very little fanfare from the media. Indeed, the significance of the even was only truly realized within the ranks of the 18th FBW itself. (Source: F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea, Warren Thompson, 1999, p29)

The 67th converted to F-86Fs. At first, the l8th’s pilots learned fighter-interceptor tactics before relearning their previous fighter-bomber duties. According to an article by Warren Thompson, “Classroom instruction was strictly business, with as many as three different classes going on at the same time, eight hours a day, seven days a week. The fast pace enabled all of the 18th’s pilots to be checked out in the new aircraft by Feb. 25, only 49 days after training began and only 32 days after the final Mustang mission.”

F-86F with early 18th FBW Tail Marking (1953)

(NOTE: Red stripes indicate the 67th FBS; Yellow Stripes indicate 12th FBS)

(F.G. Smart, F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea)

January 28: The l8th Fighter Bomber Wing received its first three PAINTED F-86F Sabres. One was marked in SAAF colors and the other two in 18th FBW colored bands. The South African Air Force’s (SAAF) No. 2 Squadron, the “Springboks” (antelopes) had a springbok silhouette painted on the sides of its Mustangs. The 12th, the “Fightin’ Foxey Few” had yellow propeller spinners with shark’s teeth on their noses like the Flying Tigers. The 67th, the “Fightin’ Cocks,” had red spinners with a rooster logo. Sabres continued to be delivered until the last Sabre arrived on 31 March.

Foxy Few Emblem on Squadron Ops Bldg (1953)

(Gene Buttyan, F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea)

The unofficial nickname 12th FBS “Foxy Few” logo appeared on the tails of the 12th FBS F-86s as well as on “Foxy Few” patches, mugs — and even signs on the Operations Building. The wing proclaimed its presence by posting a sign at the base’s main gate stating: “18th Fighter Bomber, Best Damn Fighter Group in the World”. (Source: Korea War Project: 12th FBS and Korea War Project: 67th FBS.) The 12th FBS was the only squadron that did no use an official emblem during the fighter-bomber era of the Korean War. Instead, its personnel chose to keep the “Foxy Few” logo that had been created soon after the unit had arrived in Korea from Clark AFB, in the Philippines, in July 1950. The emblem had been designed by legendary Mustang pilots “Spud” Taylor and “Chappie” James. (Source: F-85 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea, Warren Thompson, 1999, p 26)

Foxy Few Emblem on Aircraft (late 1953)

(Ken Smith, F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea)

11 February 1953: – General Maxwell D. Taylor replaces General James A. Van Fleet at Eighth Army.

22 February 1953: First mission was flown with part of the 4th. Sabre Jet Classics stated: “It was a MiG Sweep along the Yalu flown by the commanders of the three squadrons in the 18th Group. Major Jim Hagerstrom, CO of the 67th Squadron led the flight, with Commandant Gerneke as no. 2, Colonel Maurice Martin, new CO of the 18th, was no. 3, and Major Harry Evans, CO of the 12th Sq., flew no.4. Although several flights of MiGs were called out, combat with the speedy Russian jets was not accomplished.”

25 February 1953: On 25 February the 18th Wing flew its first combat mission with Sabres — a four-plane flight which tacked on to a Yalu sweep.

4 March 1953: The 18th Wing was in action, but Colonel Perego was dissatisfied with the progress that many of his conventional pilots were making. Believing that enough time had been wasted in an effort to qualify men who lacked aptitude, Colonel Perego reassigned 30 pilots to other duties in the Fifth Air Force on 4 March. (Source: USAF in Korea, Robert F. Futrell, p638)

5 March 1953: – With the death of Joeseph Stalin, the new Soviet Premier Georgi Malenkov speaks of a new peaceful coexistence.

March 1953: The 18th FBW faced many difficulties in transitioning to the F-86Fand was only flying fighter-bomber missions. One of the first problems faced by the wing following the retirement of the F-51 was twhat to do with the many high-time Mustang pilots that polulated the trio of squadrons within its charge. The process of retraining and then ‘checking out’ pilots in the Sabre was very costly, and if the USAF could not get a certain number of missions from a pilot after he had completed the training regimen, then he was considered to be a poor investment. Therefore, it was decided that any Mustang pilot that had flown less than 50 missions in Korea had to transition onto the Sabr, regardless of how he felt about shifting from a piston- to jet-engined fighter. (Source: F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea, Warren Thompson, 1999, p30)

F-80C trainer (early 1953)

(NOTE: At first, F-80s were borrowed from Suwon and Kunsan.

Later each squadron had one F-80C for training.)

(Kenneth Koon, F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea)

According to an article by Warren Thompson, “Many of the 18th FBW’s pilots were close to finishing their required 100 missions. It wouldn’t have been logical for them to go through an extensive ?and expensive ?training period in the new Sabre only to rotate back to the United States after a few missions. Instead, pilots with fewer than 50 missions automatically entered the program. The rest had three options: finish their tour with a forward air control “Mosquito” squadron; become advisors to the Mustang-equipped ROKAF; or extend their tours and have a chance to fly the new Sabres.” However, there were exceptions with a small number of ‘top-timers’ volunteered for extensions of their tours to transition to the fighters.

Major Howard Ebersole in Cockpit (1953)

(Howard Heiner, F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea)

However, a different story is told by a Training Supervisor, Maj. Howare R. “Ebe” Ebersole, at Sabre Pilots: 18th FBW Transition. He stated that on 2 March 1953, many of the F51 pilots who were anticipating combat in F-86s were told they were to be transferred either stateside if they had 75 missions — or become F-86 “advisors” to the T-6 FACs. There were some very unhappy troops and supposedly shots were heard being fired through ceilings that night — though no one was hurt. On 4 March 1953, the 12th FBS received 16 fresh F-86 pilot training graduates — all Second Lieutenants. They filled the 12th FBS squadron’s table of organization for the allotted number of pilots. By March 31st, the 12th Squadron had 25 F-86Fs. The 67th reached its full complement of Sabres by April 17. Jet trained pilots from Nellis Air Force Base soon began replacing the Mustang pilots of the 18th. (See 8th FBW: for details of F-86F.) (See TROA: “A Wing and a Prayer” for an excellent article by Warren Thompson.)

Maj. Flamm D. Harper, 18th FB Operations Officer and experienced interceptor type brought in to train personnel, stated: “Despite the naysayers of the new fighter-bomber F-86 variant, the Sabre was an excellent “mud-mover”, for it could carry two 1000-lb bombs, two external fuel tanks and 1800 rounds of 0.50-cal to any target in North Korea. Due to its speed, the jet took us far less time to accomplish the missions. We could also carry napalm, but we were never tasked to do so. We dis some skip bombing and speed did not prove to be a problem at all.” (Source: F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea, Warren Thompson, 1999, p38)

The test flights confirmed the initial impressions of combat pilots in Korea. The MiG-15 was faster than the F-86A and F-86E at altitudes above 30,000 feet, but slower at lower altitudes. Early F-86Fs were superior in speed to the MiG only up to 35,000 feet, whereas the “6-3″ F-86Fs were faster than their MiG opponents all the way up to the Sabre’s service ceiling.

One of the primary advantages of the MiG over the Sabre was its 4000-foot advantage in service ceiling. It would often happen that F-86s would enter MiG Alley at 40,000 feet, only to find MiGs circling 10,000 feet above them. There was nothing that the Sabre pilots could do unless the MiGs decided to come down and do battle. The high-flying MiGs could pick the time and place of battle, and their higher speed at high altitudes enabled them to break off combat at will when things got too tight. Many a MiG escaped destruction by being able to flee across the Yalu where the Sabres were forbidden to pursue.

F-86F Instrument Panel (1953)

(Ken Smith, F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea)

The Sabre was much heavier than the MiG and had a superior diving speed. Both the MiG and the F-86 could go supersonic in a dive, but the Sabre was much more stable than the MiG in the transonic speed regime. One way for a Sabre to shake a MiG sitting on its tail was for the F-86 pilot to open his throttle all the way up and go over into a dive, pulling its pursuer down to lower altitudes where the F-86 had a performance advantage. Above Mach 0.86, the MiG-15 suffered from severe directional snaking, which made the aircraft a poor gun platform at these high speeds. Buffeting in the MiG began at Mach 0.91, and a nose-up tendency initiated at Mach 0.93. The high-speed stability problems of the MiG-15 were so severe that it was not all that uncommon for a MiG to go into the transonic regime during an air battle, only to lose its entire vertical tail assembly during violent combat maneuvering. The rate of roll of the MiG was too slow, and lateral-directional stability was poor at high altitudes and speeds.

One of the most serious weaknesses of the MiG-15 was its tendency to go into uncontrollable spins, especially in the hands of inexperienced pilots. Many Sabre victories in Korea were scored without the F-86 pilots ever having to fire their guns — they merely forced their MiG opponents into spins from which their pilots could not recover. An experienced MiG pilot could get himself out of a spin, but the aircraft was somewhat unstable and lacked good stall warning properties.

The turning radius of the MiG was good, somewhat better than that of the F-86A, E and early F. However, this advantage was largely eliminated by the advent of the “6-3″ wing of the later F-86F. The good turning radius of the MiG was compromised by poor stalling characteristics. These bad stalling characteristics could get a green MiG pilot into serious trouble during the stress of a dogfight, causing his fighter to suddenly stall, go into an uncontrollable spin, and fall out of the sky.

MiG 15b

In contrast, the spinning characteristics of the Sabre were excellent, and gave most pilots no trouble at all. If the F-86 was forced into a spin, recovery was usually effected by simply neutralizing the controls.

The MiG-15 armament of one 37-mm N-37 cannon and two 23-mm NR-23 guns was designed for attacking bombers, and was not really intended for use against fighters. Forty rounds of 37-mm ammunition and 160 rounds of 23-mm ammunition were carried, a rather low ammunition capacity. The 37-mm gun fired at a rate of 450 rpm, whereas the 23-mm guns each fired at a rate of 650 rpm. The MiG’s armament had a good punch, but the rate of fire was too slow to make it effective against nimble, rapidly-maneuvering fighters. In contrast, the F-86′s armament of six 0.50-in machine guns had a rapid firing rate and the aircraft carried an ample supply of ammunition. However, the machine guns of the Sabre lacked the stopping power of the MiG’s cannon. It was not uncommon for a Sabre pilot to empty all 1600 rounds of his ammunition at a MiG, only to see it escape unscathed.

The gunsight of the MiG-15 was of the simple gyro type, similar to that of the early F-86A. It lacked any radar ranging capability. The radar ranging gunsight of the later Sabres made the F-86 a much more accurate gun platform than the MiG, but this accuracy was sometimes wasted because of the low weight of fire from the machine guns.

The MiG was much lighter than the Sabre, weighing only 11,070 pounds loaded. The take off run to clear a 50-foot obstacle was only 2500 feet, as compared with 3660 feet for the F-86A.

Internal fuel capacity of the MiG was 372 US gallons, compared with 435 gallons for the Sabre. This gave the MiG a range of 480 miles, which could be increased to 675 miles with drop tanks.

During the Korean War, 792 MiG-15s were destroyed by F-86 pilots, with 118 probables being claimed. 78 Sabres were definitely lost in air-to-air combat against the MiGs, with a further 13 Sabres being listed as missing in action. This is about a ten-to-one superiority. From this result, one might naturally conclude that the F-86 was the superior fighter. However, a factor which must also be considered is the relative level of experience and competence of the opposing pilots. The US Sabre pilots were all highly trained and competent airmen, many of whom had extensive World War 2 combat experience. With the exception of some Russian World War 2 veterans who flew MiG fighters in Korea, the MiG pilots were often sent into combat with only minimal flying experience. MiG pilots often exercised poor combat discipline. During the course of battle, MiG pilots would often break off into confusion and panic, firing wildly, and leaving their wingmen unprotected. Often, a MiG pilot in trouble would eject from his plane before anyone actually shot at him. Many MiG pilots were so inexperienced that in the heat of battle they would end up getting themselves into uncontrollable spins and crashing. At times, MiG pilots would fire their cannon in an attempt to lighten their loads, without really aiming at anything. Most of the MiG pilots were extremely wary of combat, and usually did not attempt to fight unless they saw an advantage opening up. In contrast, the Sabre pilots were aggressive and eager for combat, and wanted nothing more than for the MiGs to come over the Yalu so that they could add to their scores.

So, which plane would you rather be sitting in, the MiG-15 or the F-86? Perhaps Chuck Yeager said it best–”It isn’t the plane that is important in combat, it’s the man sitting in it.” (Source: Baugher site: F-86)

12 March 1953: Training of the SAAF pilots continued into February and by 12 March the squadron was once more flying sorties. The squadron was mainly employed in a ground attack role as the Sabre proved to be an excellent aircraft for dive-bombing, carrying two 1000lb bombs or napalm and rockets.

27 March 1953: Assigned as the CO of the 67th Fighter Bomber Squadron, 18th Fighter-Bomber Wing (FBW), Maj. James P. Hagerstrom destroyed his fifth MiG to become the twenty-eighth Korean War jet air ace. Hagerstrom, of the Texas Air National Guard, scored 6.5 MiG kills to become the first and only ace from the l8th Fighter Bomber Group. He had earlier gotten two while flying with the 334th Fighter Interceptor Squadron, 4th Fighter Interceptor Group, giving him a total of 8.5. He was transferred from the 4th FIG to make for the lack of experience in the 18th FBG with the F-86 transition — and became the only Fighter Bomber ace of the Korean War. (Source: AFHRA) (NOTE: The F-86 static display near the Doolittle Gate at Osan AB is supposed to be a representation of Jim Hagerstrom’s aircraft, “MiG Poison.” Hagerstrom was promoted to Major in 1950, Lt. Col in 1953 and Colonel in 1958 based on being an “ace.” For Hagerstrom, flying combat missions in Korea was a once-in-a-lifetime career opportunity. He did everything he could to prepare himself for such a task: he started running on the beach, taking courses over and over again on the A-4 gun sight, and reading all the intelligence reports he could get his hands on at Nellis AFB. (Source: Officers in Flight Suits, John Darrell Sherwood, 1996, p70.) While at Osan, he was did not imbibe before a mission to ensure he would be “100 percent.” There was some criticism that he would dump his bomb load as soon as possible and head to MiG Alley. An assignment to the 18th FBW from the 4th FIW was not in his game plan — and he was hell-bound to be an ace. Aces were willing to “go it alone” and even break standard rules of engagement for the sake of a kill. Hagerstrom once flew fifteen feet over the alert pad at Antung at nin-tenths the speed of sound just “trying to get the MiGs off the ground. (Source: ibid, p89) Hagerstrom before he left the states had a special pair of half-mirrored distance glasses made which enabled him to see at twenty feet what an ordinary person would see at ten. The optometrist told him they might permanently ruin his eyes, and he replied: “I don’t give a shit.” (Source: ibid, p84.) In March 1953, he knew he was going to transferred to fighter-bombers or out of theater with only 4.5 kills, so he desparately gave it the old “college try to get one more to be an ace. He shot down two outside Antung. On his last day in Korea, he was in dress-blues awaiting his C-47 out when an alert was called and he flew that day to claim one more. (Source: ibid, pp89-90))

Maj. James P. Hagerstrom after MiG kills

while with 4th FIS (Dec 1952)

Maj Hagerstrom outside Ops Bldg (Early 1953)

(NOTE: Notice the early tail marking for 18th TFW on a/c in background)

(Don McNamara, F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea)

Lt Robert Cassatt poses

in front of Maj. Hagerstrom’s F-86F “Mig Poison”

(which bears 6.5 red stars on its canopy rail) (Early Summer 1953)

(Robert Cassatt, F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea)

April 14: The first dive-bomb mission was flown on 14 April.

28 March 1953: – North Korean premier Kim Il Sung and Chinese commander in chief Peng Teh-huai agree to the POW exchange proposed by General Clark.

March 30 – Chinese Foreign Minister Chou En-lai indicates that the Red Chinese will accept the Indian Rsolution of December 1952. Thus, truce talks resume at Panmunjom.

31 March 1953: The last of 25 F-86s to the 12th FBS delivered to Osan. Within a week both No. 2 Sqn and the 67th FBS could also boast their full complement of the new ‘Dash-30s’! (Source: F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea, Warren Thompson, 1999, p31) With many new replacement pilots from the United States and eventual arrival of more Sabres, the 12th Squadron reached unit strength on 31 March and the 67th Squadron attained a similar status on 7 April 1953. (Source: USAF in Korea, Robert F. Futrell, p638)

Last week of March to April 18 – The Battles of Old Baldy, Eerie, and Pork Chop Hill all take place.

April 1 – Two squadrons (428th & 429th FBS) of the 474th FBG of Kunsan AB (K-8) administratively swapped (on paper) with two squadrons of the 49th FBG (7th & 8th FBS) of Taegu (K-2) to form Taegu’s new 58th FBW (Reinforced). The 430th FBS (474th FBG) transferred to Taegu.

April 1953: Average Number of F-86Fs Assigned: 45 / Total Hours of Flying Time: 1933.25 / Average Hours per F-86-F: 43 / Number of Sorties Flown: 623 / Percent of F-86Fs In-commission: 83% / Total F-86Fs Lost in Combat: 0 / Total F-86Fs Lost (other reasons): 0 / Fuel Consumed (Gallons): 819,415 / Engine Changes: 7 / 0.50-cal Rounds Expended 23,631 / Napalm: 0 / 5-in Rockets Expensed: 0 / 500-lb Bombs: 569 / 1000-lb Bombs: 0 / 260-lb ‘Frag’ Bombs: 0 / AN-M76 Incendiary Bombs: 0 / Major Inspections: 17 / F-86Fs Battle Damaged (Major): 1 / F-86Fs Battle Damaged (Minor): 0 (Source: F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea, Warren Thompson, 1999, p89)

Early Morning Briefing with 12th and 67th on the left and 2d SAAF on the right (1953)

(Archie Buie, F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea)

20 to 26 April 1953: – There is an exchange of sick and wounded POW’s at Panmunjom know as Little Switch.

26 April 1953: – Full plenary talks resume at Panmunjom.

27 April 1953: The first close support of troops along the MLR, was flown on 27 April. Sabres from the 18th Group, with top cover from 4th and 51st Group Sabres, knocked Radio Pyongyang (Ping-Pong Radio) off the air during the May Day attack led by General Glenn Barcus, boss of 5th Air Force.

According to The U.S. Air Force in Korea (p637), “Because the Sabre transition program was running behind schedule, General Barcus amended his instruction that the wings would qualify all of their pilots in fighter-interceptor tactics before beginning fighter-bomber training. On 1 April the 18th Wing began bombing practice and the 8th Wing integrated bombing tactics with its interceptor training. On 14 April 8th Wing pilots flew the first F-86 fighter-bomber mission, and on 14 April the 18th Wing made its debut with F-86 fighter-bombers.”

During this time period, morale boosting victory rolls and 100th Mission flyovers to “buzz” the runway was permitted — much to the delight of the ground personnel. In ‘BUZZ JOB!’ ‘THE TOUR IS OVER’ by ‘Ebe’ Ebersone and Hans Degner, “After they were down, Hans and I went north of K-55, and I requested a “last mission low pass”. We were ‘cleared as requested’, and switched to our ‘discrete frequency’ to coordinate our pass. Flying north to south, Hans on my right wing, we straddled the tower at their glass-cab height. We were ‘pushing the Mach’ at near full throttle! Hans peeled tight to the right, and I broke left We met head-on, each on his right hand side of the runway, about mid-field, did a loop, joined up for a couple of low, fast passes over the maintenance troops, did a victory roll in formation, came In and landed. What could be more fun than that?”

67th FBS (1953)

(Dwight Lee, F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea)

May 1953: Average Number of F-86Fs Assigned: 44 / Total Hours of Flying Time: 2054 / Average Hours per F-86-F: 47 / Number of Sorties Flown: 1234 / Percent of F-86Fs In-commission: 91% / Total F-86Fs Lost in Combat: 1 / Total F-86Fs Lost (other reasons): 3 / Fuel Consumed (Gallons): 942,069 / Engine Changes: 4 / 0.50-cal Rounds Expended: 104,780 / Napalm: 4 / 5-in Rockets Expensed: 0 / 500-lb Bombs: 982 / 1000-lb Bombs: 1116 / 260-lb ‘Frag’ Bombs: 0 / AN-M76 Incendiary Bombs: 0 / Major Inspections: 25 / F-86Fs Battle Damaged (Major): 1 / F-86Fs Battle Damaged (Minor): 2 (Source: F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea, Warren Thompson, 1999, p89)

3 May 1953: – The rest of the sick and wounded POW’s are exchanged.

13 May 1953: – Raid on Toksan Dam. Dramatic strike of 58th FBW F-84s destroys a major irrigation system. 5 miles of rice fields and railroad tracks/highways destroyed. Attacks continue for the next few weeks.

31 May 1953: The 67th Squadron lost an entire flight on May 31, 1953. “Beer Flight” (all their flights were named after drinks, such as Scotch, Gin, Vodka, Beer) had two fatalities and lost all four aircraft in one day. Leader “Tex” Beneke was killed on takeoff, “Smo” Smotherman was killed in flight, and Lieutenants Varbie and Carmichael crashed on landing, but both survived. The call sign, “Beer Flight,” was permanently retired.

June-July 1953 In June and July the communists again launched a massive offensive against the UN forces, and despite bad weather the air force was again called on to give air support to the troops, carrying out their task so effectively that the Communist offensive ground to a halt and their delegates at the peace talks decided the time had come to end the war. In order to prevent the enemy from building up its air power in the meantime, the UN aircraft continued to carry out intensive attacks.

67th FBS Flightline (1953)

(Robert Niklaus, F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea)

June 1953: Average Number of F-86Fs Assigned: 43 / Total Hours of Flying Time: 2211 / Average Hours per F-86-F: 51 / Number of Sorties Flown: 1606 / Percent of F-86Fs In-commission: 92% / Total F-86Fs Lost in Combat: 9 / Total F-86Fs Lost (other reasons): 4 / Fuel Consumed (Gallons): 959,684 / Engine Changes: 10 / 0.50-cal Rounds Expended: 241,452 / Napalm: 56 / 5-in Rockets Expensed: 0 / 500-lb Bombs: 1038 / 1000-lb Bombs: 1434 / 260-lb ‘Frag’ Bombs: 0 / AN-M76 Incendiary Bombs: 2 / Major Inspections: 1 / F-86Fs Battle Damaged (Major): 5 / F-86Fs Battle Damaged (Minor): 5 (Source: F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea, Warren Thompson, 1999, p89)

2d SAAF F-86F landing (1953)

(Dwight Lee, F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea)

2d SAAF F-86F Being Repaired with 67FBS assistance (1953)

(John Batchelder, F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea)

10-18 June 1953 The 12th Squadron lost eight pilots between June l0 and the 18th. Three were killed in action, two others became POWs, and three were lost in a C-124 crash in Japan.

18 June 1953: – South Koreans release 27,000 North Korean POW’s who refused to be repatriated. Communists then break off negotiations.

25 June 1953: – Robertson begins “Little Truce Talks” with Rhee to secure the Republic of Korea’s acceptance of armistice. Meanwhile, Chinese forces launch massive attacks against the Republic of Korea Divisions.

30 June 1953: By June 30 there were 127 pilots on the roster, with 82 percent classified as combat ready. The remaining 18 percent were new replacements coming into the wing, all of whom already had received advanced training in jets at Nellis Air Force Base but had to be checked out in the required air-to-air and ground-support tactics.

10 July 1953: – Communists return to the negotiation table after U.N. assurances that the Republic of Korea would abide by the terms of the cease fire.

11 July 1953: South Korean President Syngman Rhee agreed to accept a cease-fire agreement in return for promises of a mutual security pact with the United States.

15 July 1953 Unauthorized strike of a target near approved by a temporary Major Dee Harper results in a huge success with the destruction of a Chinese munitions buildup for a pending attack. (NOTE: Source noted: “Official USAF Historical records report the date of these occurrences as 16 June, 1953, but Harper, who was personally involved, remembers them happening somewhat later, “probably 15 July”, based upon his vivid recollection of the bail-out experience of 27 June and the two week period of his hospital stay prior to assuming the Operations Duty. There is no question concerning the veracity of the acts reported, only the conflicting dates, which could easily have stemmed from a subsequent typographical reporting error. Col. Harpers says 밽iven up?trying to set the offical USAF record straight.”) (Source: 18th Fighter Wing Association: Lt. Col. Flamm “Dee” Harper.)

But this second time he (Dee Harper) paid a higher price for his successful evasion ?while bailing out, his 멵hute barely had time to open, then collapsed as he hit the rocks alongside a cliff. Harper ended up draped over a big boulder at the foot of the cliff, with a few broken ribs and a heavy contusion to his spinal cord. He was hospitalized for two weeks after his rescue, following which he was placed on 멏NIF?status, (Duty Not Involving Flying) where he served as 18th Fighter Group Operations Officer to manage the scheduling of bomb loads and target directions for the Group뭩 three squadrons. Harper, at that time, was a Captain, serving wih a temporary ?i>Spot Promotion?to Major. It was not really tough duty by that point in time, because peace talks had begun at Panmunjom in Spring 1953, and finally showed promise of a compromised end to the vicious fighting in Korea.

Both sides appeared to be cutting back on their directed combat operations, and even though 5th AF was having trouble finding targets worthy of pre-planning, everyone seemed to have a sense of apprehension that the North Koreans were planning one final, last ditch assault to enhance their bargaining position at the peace table. Individual pilots became extra wary, and hesitated to become 몋oo aggressive? thinking they could reluctantly become ?i>the last man to die in the Korean War??br>

Late in the afternoon of June 16, 1953*, , while Lt. Col Harry Evans, 12th Sq CO, led an armed recce flight operating just North of the battlefront, they discovered a very long train of what appeared to be 밶 hundred or more cars stalled in front of a tunnel? They attacked the newly-identified targets, causing huge explosions and fires, but when they became low on fuel and had to leave the area, there still remained scores of undamaged rail cars.

?i>Near the same time*?in mid-June 1953, in the vicinity of Heartbreak Ridge, Lt. Col. C. L. Stanton, Commanding Officer of the 67th Sqdn, discovered a concentration of several thousands enemy troops?in the open, all neatly arrayed in huge rectangular formations marching along a road; his flight immediately attacked the formations and encampments with their 1000 lb bombs, rockets and machine guns, slaughtering an estimated two thousand or more of the enemy.

When the flights returned to base at Osan (K-55) from the rail and troop attacks, and reported their startling new enemy targets to Operations Officer Dee Harper, he immediately contacted Taegu뭩 Fifth Air Force Combat Operations Center for permission to promptly reload and dispatch additional aircraft to continue the attack.

As the luck of ?i>Murphy뭩 law?would have it, the 5th AF Commanding General happened to be at dinner when Harper tried to call for authorization, and no one in the Combat Operations Section would venture to interrupt the General뭩 repast with such a wild and unconfirmed report.

멑rustrated by the bureaucratic roadblock imposed by 5th Air Force Hqtrs, and the fact that his own 18th Group and Wing Commanders were not available 꿧or they were attending a conference in Tokyo 꿣ut also knowing full well that neither of the vital strategic targets would remain in place through the night, Major Flamm D. Harper made a Command Decision, on his own, to refuel and re-arm the Sabrejets, and send them back to restrike the targets immediately ?that evening and, almost unheard of in ground attack battles, they continued their dangerous air-to-ground attacks far into the dark of night?when their targets were lit only by the flames of the burning and exploding rail cars. The 18th Wing had been 멦asked?by 5th AF to fly 120 combat ?i>sorties?on that day .. (1 plane on 1 flight equals 1 sortie) and the Wing had already completed 93 of them. During the remainder of that evening and night they flew an additional 94 combat sorties, losing two aircraft, (but just one pilot) in the process of wiping out the prepared-and-ready armaments which the enemy had stockpiled to spring their final massive offensive on the following day. The Chinese battle plan was never launched; it뭩 strength had been mortally sapped by the heroic night attacks of the 18th Fighter-Bomber Wing pilots, under the forceful .. if illegal .. direction of one 멿owly?temporary Major, by the name of 멖arper?

The war petered out during the next few weeks, and the fragile truce was finally signed on 27 July, 1953. The many pilots who had bravely flown their F-86 Sabres in low level ground attacks with only their altimeters and the silhouette of hills near the burning rail cars keeping them from plowing into the ground, reveled in the success of their night뭩 work. None of them knew that all of their heroic missions that evening were 몍nauthorized? because Harper had purposely kept it from them ?not wanting to expose anyone but himself to the almost certain threat of military Courts Martial.

Only the recognition of the tremendous success of the 18th Wing뭩 missions in stemming the impending Chinese offensive prevented him from possibly being cashiered from the Air Force ?or being limited to a lifetime in the rank of Captain.

멏ee?Harper was 멵hewed out, royally?for assuming the General뭩 prerogatives ?but he had come to expect that after his Group CO told him that he, the Colonel, had suffered the very worst ass-chewing of his entire career over Harper뭩 unauthorized ?i>Decisions?

27 July 1953: At 1000 hours on 27 July 1953, the Korean Armistice agreement was signed, stopping the fighting in Korea. Throughout that final day of the war, UN aircraft roamed the skies over North Korea searching for targets of opportunity. At 2201 hours, the Armistice went into effect and all UN aircraft had Flight to be on the ground and/or south of the bomb line.

27 July 1953: – The cease fire is signed by Lieutenant General Nam Il and Lieutenant General Wiliam Harrison at 10:00am at Panmunjom. Twelve hours later all fighting ceases. (NOTE: See Armistice Agreement, Volume I — U.S. (as head of UN Forces), North Korea and China signed, but South Korea refused to sign this document. Technically, South Korea is still in a state of war with North Korea. To gain South Korea’s acceptance of the Armistice, the U.S. signs the 1953 Mutual Defense Treaty Between the Republic of Korea and U.S.)

B-26 from the 8th Bomb Squadron (L-NI) flies the last sortie of the war. The honor of the last mission was given to the 8th because it flew the first missions over North Korea.

4 September 1953: – The processing of POW’s for repartriation begins at Freedom Village, Panmunjom.

1 October 1953 No. 2 Squadron ceased all operational flying and began turning their Sabres over to 5th AF units still operational in Korea. The last aircraft were returned on 11 October, and all South African personnel had departed Korea by 29 October.

The United Nations acceded to the request of the United States to intervene militarily on the side of South Korea. On 12 August 1950, the South African government announced its intention of placing No. 2 Squadron, the so-called “the Flying Cheetahs” of the South African Air Force at the disposal of the United Nations. The offer was accepted, and on 26 September 1950, 49 officers and 206 other ranks, all volunteers, left from Durban for Johnson Air Base in, Yokohama, Japan, prior to their deployment in Korea. All these men were seasoned pilots and technicians having an outstanding World War II record from operations in Eastern Africa, Ethiopia, Sicily, Italy and the Middle East.

2 Squadron had a long and distinguished record of service in Korea flying F-51D Mustangs and later F-86F Sabres. Their role was mainly flying ground attack and interdiction missions as one of the squadrons making up the USAF’s 18th Fighter Bomber Wing.

The first flight of four F-51D Mustangs departed for Korea on 16 November 1950 and the first operational sortie was flown three days later from K9. This was at a stage when the United Nations forces were retreating in front of the advancing enemy. In freezing cold and poor weather, the aircraft had to continue operating and be maintained and armed in the open, moving from K-24 (Pyongyang East Air Field) to K-13 (Suwon Airbase), K-10 (Chinhae Airbase) and finally K-55 Airbase at Osan in January 1953, which became the all jet fighter base for the 18th Fighter Bomber Wing. Here the squadron immediately started to convert to the Canadian F-86F Sabre jet fighter. On 11 March 1953 the squadron flew it first operational sortie with the F-86F Sabre. The Squadron now flew, in addition to its ground attack role, high-level interdiction and standing patrols along the Yalu River.

The cease-fire was signed at Panmunjom at 11:00 hours on 27 July 1953. During the Korean conflict the squadron flew a grand total of 12 067 sorties.

2SAAF F-86

A total of 243 Air Force officers and 545 other ranks served in Korea. 34 pilots out of 152 and 2 other ranks gave their lives. Eight prisoners of war were returned. Aircraft losses amounted to 74 out of 97 Mustangs and four out of 22 Sabres.

On 31 October 1953, the last South African Force left Korea.

The Squadron received the United States Presidential Citation, the Korean Presidential Citation and the USAF Unit Citation. Individual medals were 2 Silver Stars, 50 Distinguished Flying Cross (DFCs), 1 cluster to the DFC, 40 Bronze Medals, 176 Air Medals, 152 clusters to the Air Medal and 1 Soldier Medal.(Source: 2 Sqdn SAAF )

2d Sqdn SAAF F-86 (1953) (Bob Spiwak)

As the SAAF was to leave, the Commanding Officer of the 18th Fighter Bomber Wing, under which command the squadron was under, issued a directive at the end of the war that: “In memory of our gallant South African comrades, it is hereby established, as a new policy that at all Retreat Ceremonies held by this Wing, the playing of our National Anthem shall be preceded by playing the introductory bars of the South African National Anthem, ‘Die Stem van Suid-Afrika’. All personnel of this Wing will render the same honours to this Anthem as our own.” (Source: 2 Sqdn SAAF (Flying Cheetahs) in Korea ) The Flying Cheata’s in Korea by Deeermot Moore and Peter Bagshore states, “Two bars of the SA National anthem is always played before the US National anthem on official parades to this day.”

——————————————————————————–

Life in the 18th FBW

In addition to being more dangerous, the mission of the fighter bomber tended to be less rewarding than that of the fighter-interceptor. A village bombed was not the same as a MiG destroyed — no visible status symbols were awarded and rarely was the press interested in hearing bomber stories. Aces such as James Jabara and Joseph McConnell had their pictures plastered in such national maagazines as Life, Look, and Time. Fighter-bombers, on the other hand, only received attention in service oriented journals, such as the Air Force Times and Air Force Magazine napalming a village or a suspected troop concentraiotion was hardly as romantic as shooting down a sleek MiG. No title, parties, or awards were given for bombing five villages. In fact, a fighter-bomber only received a party after his death or his hundredth mission — which ever came first. The hundredth-mission party varied from squadron to squadron, but it generally consisted of a “victory pass” over the base by the hundredth-mission pilot, followed by a photo session and a champaigne reception on the tarmac. The more common party, though, was a “shoot-down party.” According to Perrin Gower: “Every time someone got shot down, they threw a party and got completely stoned. Ostensibly it was a wake, but really it was a celebration to celebrate the fact that it wasn’t you.” Survival, in short, was the major reward for the fighter-bomber and the only status symbol he could look forward to during his tour. (Source: Officers in Flightsuits, John Darrell Sherwood, 1996, pp 102-103)

While fighter-interceptor pilots also sported baseball caps in Korea, the phenomenon was even more popular in the fighter-bomber units. Each squadron custom-designed and ordered its own cap from Japanese manufacturers. colorful and erotic unit logos were vital part of morale building. The symbol … for the South African squadron, a “Flying Cheetah.” Other squadrons adopted a sewual theme asuch as “the Foxy Few,” the logo of the 12th Squadron of the 18th Figheter Bomber Wing. Heiner’s squadron, the “Fighting Cocks,” went so far as to have Walt Disney design its logo — a rooster with boxing gloves. The logo was emblazoned on aircraft, flight suit patches, and even squadron beer mugs — mugs which were proudly hung in the “The Cockpit” (the Osan officers’ club). (Source: ibid, pp 110-111)

In addition to developing colorful logos and flying missions, fighter-bomber wing, goup, and squadron commanders relied heavily on floklor as a vehicle for instilling their outfits with pride. The 67th Fighter-Bomber Squadron, for example, took pride in the fact that their unit was organized explicity for duty in the Korean War. According to their squadron newsletter, the Fighting Cocks were “conceived in haste, born in obscurity, and have risen from the unknown to write a fateful page in history.” Interestingly enough, this fateful page concentrates more on the squadrons’s close air support missions that its interdiction attacks. For the fighter-bomber, supporting frontline troops was seen as much more honorable than napalming Korean villages or cutting railroad tracks. The newsletter emphasized throughout that the contribution of the squadron “cannot be expressed in words of praise, but only in the hearts of the men in the front lines, who daily watched the squadron’s relentless attacks against the enemy weaken and drive him to cover.” (Source: ibid, pp 112-113)

Like the 67th Squadron, the Foxy Few of the 12th Squadron relied heavily on unit history to upld the morale of the group. They boasted that theirs was the first official USAF combat squadron to see action in Korea. The Foxy Few also traced their lineage back to the World War II Flying Tigers. Consequently, they painted tigers’ teeth on their aircraft — a tradition that was also carried over to the Vietnam and Gulf Wars. (Source: ibid, p113)

18th FBW Officer’s Club (1953)

(Robert Niklaus, F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea) (NOTE: Murals along the wall depicts various facets of the Wing’s history.)

Red Scarf Club — 67th FBS Officers’ Lounge (1953)

(Robert Niklaus, F-86 Sabre Fighter-Bomber Units Over Korea)

Two institutions that helped foster cohesiveness in the unit was the squadron dayrooms and officers’ club.

The dayroom was the building where the indiidual squadrons posted flying assignments and unit statistics. This hut was the nexus for on- and off- duty pilots during the day. It was one of the few places on base reserved squadron activities alone: the officers’ clubs were shared by all officers of a wing. As a consquence, each squadron attempted to fix up its dayrooms and transform them from drab operation buildings to comfortable flight lounges. Each squadron had its own beer mugs with the squadron insignia emblaxoned on them. An example was the 67th FBS “Red Scarf” Lounge pictured above. The 12th FBS lounge was named “The Cockpit.” According to Kenneth Koon of the 12th FBS, That’s all there was — the mess hall was for eating.” Kenneth Koon, a light drinker, typically would have a coulple of martinis at his club when he was not flying. (NOTE: Flying officers would cure hangovers by turning the oxygen to 100 percent — a sure cure for queasiness and hangovers.) (Source: Officers in Flightsuits, John Darrell Sherwood, 1996, pp 123-126)

While the dayroom was the primary place for pilots to relax and socialize during the day, the officers’ club or “o club,” was where most pilots spent their evenings. Unlike the dayroom, the o club served no operational purpose — it was used solely for drinking, eating, and socializing. In fact, it was the central party place on most bases — a plce to indulge in the primary off-hours ritual of flight suit culture: drinking. Unlike its stateside counterpart, the O-club in Korea was not afforded much respect and was frequently trashed by rowdy pilots. Colonel Martin, Wing Commander at Osan, is uoted as saying, “Korea was the easiest place in the world to become an alcoholic: it was exttremely cheap and available everywhere.” (ibid, p125)

Lack of other activities as well as a shortage of women on bases made “booze the primary recreational activity.” Whereas beer was bought locally, liquor was imported to bases from the rear-echelon maintenance bases in Japan.

No group of flyers had a more notorious reputation for drinking than the South African Cheetah Squadron who definitely consumed the most booze but handled it better than most of their USAF counterparts. The Cheetahs turned most of their squadron debriefings into two or three mission-whiskey bottle parties. (NOTE: SEEKING INFORMATION ON NCO/ENLISTED CLUBS.) It is known that during this period the officers could procure and drink hard liquor (distilled spirits), while the enlisted were limited to “green beer.” The beer was first shipped up from Pusan, but later when the brewery in Yongdong-po was back in operation, the supply was from Seoul. We are guessing that the local NCO club was mixed-service and if it was like other areas had a crap game in operation 24-hours a day. Lower ranks (E-3 and below) were served in the Airmen’s Club.

Pheasant Hunting (1953)